Success in Section 1983 Appeals— Litigation Tips and Strategies

Posted

08 Jul 2022 in Tips and Tactics

Occasionally an attorney will propose that the parties stipulate to the meaning of a relevant statute. Such stipulations have no legal force and will be disregarded by the court. Numerous cases so hold across the United States: “Parties to a dispute cannot stipulate to the law and assume that the court will follow blindly an incorrect interpretation of the law, especially in an unsettled and everchanging area.” Carlile v. South Routt School Dist. RE-3J, 739 F.2d 1496, 1500 (10th Cir. 1984) “Parties...

If you have the responsibility to create part of the record, select a page numbering system that makes sense so no pages have the same number. Create a meaningful index to the record. For example, if a document has an odd or misleading title, provide that title and, in brackets] a few accurate, neutral, descriptive words. Identify the declarant or witness if that information is not in the title. Provide copies of the index in the brief and in each volume of the record, marking which documents are in which volume.

Cite to the record for every point. Dominguez v. Financial Indemnity Co., 183 Cal.App.4th 388, 392 n.2 (2010) (“because FIC’s brief fails to provide a citation to the appellate record for these facts, we do not consider them”); AdvanceMe, Inc. v. Finley, 275 Ga. App. 415, 620 S.E.2d 655, 657 (2005) (“It is not the function of this court to cull the record on behalf of a party”). It almost goes without saying that you should cite accurately to the page with the relevant material. Scott v. Bank of America, 292 Ga. App. 34 , 663 SE 2d 386, 387 (2008) (“while the parties cite to the appellate record, many of the page numbers cited are incorrect”). Cite to the record by page and line, if the lines are numbered, even if that specificity is not required. Skinner v. State, 83 Nev. 380, 432 P.2d 675, 384 & n.4 (1967); Anderson v. Meyer Broadcasting Co., 630 N.W.2d 46, 50 (N.D. 2001). Cite by page and paragraph or use terms like “start,” “middle,” and “end” if there are no line numbers.

If you have the responsibility to create part of the record, select a page numbering system that makes sense so no pages have the same number. Create a meaningful index to the record. For example, if a document has an odd or misleading title, provide that title and, in brackets] a few accurate, neutral, descriptive words. Identify the declarant or witness if that information is not in the title. Provide copies of the index in the brief and in each volume of the record, marking which documents are in which volume.

Cite to the record for every point. Dominguez v. Financial Indemnity Co., 183 Cal.App.4th 388, 392 n.2 (2010) (“because FIC’s brief fails to provide a citation to the appellate record for these facts, we do not consider them”); AdvanceMe, Inc. v. Finley, 275 Ga. App. 415, 620 S.E.2d 655, 657 (2005) (“It is not the function of this court to cull the record on behalf of a party”). It almost goes without saying that you should cite accurately to the page with the relevant material. Scott v. Bank of America, 292 Ga. App. 34 , 663 SE 2d 386, 387 (2008) (“while the parties cite to the appellate record, many of the page numbers cited are incorrect”). Cite to the record by page and line, if the lines are numbered, even if that specificity is not required. Skinner v. State, 83 Nev. 380, 432 P.2d 675, 384 & n.4 (1967); Anderson v. Meyer Broadcasting Co., 630 N.W.2d 46, 50 (N.D. 2001). Cite by page and paragraph or use terms like “start,” “middle,” and “end” if there are no line numbers.

instead of substituting a paragraph mark.

Choose block quotes carefully and sparingly. Judge Alex Kozinski remarked: “Whenever I see a block quote I figure the lawyer had to go to the bathroom and forgot to turn off the merge/store function on his computer.” Kozinski, The Wrong Stuff, B.Y.U.L. Rev. 325, 329 (1992). Given the danger that long block quotes may not be read, paraphrase the less critical material to shorten the block. Write the lead in to the block to reveal its importance. If the block is important because it states the three elements of this or the five tests for that—then add letters or numerals in brackets or otherwise format to assist the reader. Although a textual repetition of the content immediately following the block is likely to offend the reader, the points can be worked into the text at a later opportunity.

instead of substituting a paragraph mark.

Choose block quotes carefully and sparingly. Judge Alex Kozinski remarked: “Whenever I see a block quote I figure the lawyer had to go to the bathroom and forgot to turn off the merge/store function on his computer.” Kozinski, The Wrong Stuff, B.Y.U.L. Rev. 325, 329 (1992). Given the danger that long block quotes may not be read, paraphrase the less critical material to shorten the block. Write the lead in to the block to reveal its importance. If the block is important because it states the three elements of this or the five tests for that—then add letters or numerals in brackets or otherwise format to assist the reader. Although a textual repetition of the content immediately following the block is likely to offend the reader, the points can be worked into the text at a later opportunity.

identify the right starting place and the steps required to travel from the starting point to the desired end, avoiding the tendency to slide over or combine them.

Briefs using this model should provide all forms of authority needed to convince the judge to take the next step. Possible evidentiary issues need to be resolved; substantive questions need to be answered or shown to be inapplicable. As each step is explained and answered, the next step can be introduced and its issues and questions answered. At the end, the table of contents alone can walk the reader through the points to the desired ruling.

Once the steps are identified, the writer may elect to address evidentiary issues as a group, at the beginning or end of the brief. Alternatively, a writer may prefer to brief all issues presented by one step before turning to the next step. No matter which technique is adopted, work on later steps will often turn up cases and points that can strengthen the earlier steps. As work progresses, a single step may be perceived as comprising several steps, requiring additional reworking.

identify the right starting place and the steps required to travel from the starting point to the desired end, avoiding the tendency to slide over or combine them.

Briefs using this model should provide all forms of authority needed to convince the judge to take the next step. Possible evidentiary issues need to be resolved; substantive questions need to be answered or shown to be inapplicable. As each step is explained and answered, the next step can be introduced and its issues and questions answered. At the end, the table of contents alone can walk the reader through the points to the desired ruling.

Once the steps are identified, the writer may elect to address evidentiary issues as a group, at the beginning or end of the brief. Alternatively, a writer may prefer to brief all issues presented by one step before turning to the next step. No matter which technique is adopted, work on later steps will often turn up cases and points that can strengthen the earlier steps. As work progresses, a single step may be perceived as comprising several steps, requiring additional reworking.

On occasion, however, trial counsel may have acted so unprofessionally or ignorantly as to be the target of strong remarks by the appellate court. In this case, the appellate court should and often does inform readers of its decision that the same attorney did not appear in both courts.

On occasion, however, trial counsel may have acted so unprofessionally or ignorantly as to be the target of strong remarks by the appellate court. In this case, the appellate court should and often does inform readers of its decision that the same attorney did not appear in both courts.

Failure to comply may delay the appeal or result in other sanctions. For example, California provisions declare: “No judgment or relief, temporary or permanent, shall be granted or opinion issued until proof of service of the brief or petition on the Attorney General and district attorney is filed with the court.” Cal. Bus. and Prof. Code §§17209, 17536.5; accord, id. §16750.2.

Federal law also requires notice and grants a right of intervention to the United States Attorney General or the California Attorney General, respectively, when the constitutionality of federal or state statutes affecting the public interest is challenged in federal litigation to which the federal or state government or their agencies or employees are not already parties.

Failure to comply may delay the appeal or result in other sanctions. For example, California provisions declare: “No judgment or relief, temporary or permanent, shall be granted or opinion issued until proof of service of the brief or petition on the Attorney General and district attorney is filed with the court.” Cal. Bus. and Prof. Code §§17209, 17536.5; accord, id. §16750.2.

Federal law also requires notice and grants a right of intervention to the United States Attorney General or the California Attorney General, respectively, when the constitutionality of federal or state statutes affecting the public interest is challenged in federal litigation to which the federal or state government or their agencies or employees are not already parties.

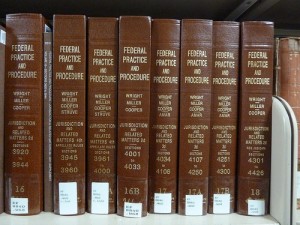

Rules do not normally determine the merits, although rules provide the structure or framework within which the merits can be considered fairly to both sides. Not surprisingly, judges typically know the applicable rules quite well. The judge may have drafted the local rule specifically to address an issue arising with some frequency in that judge’s courtroom. Or the judge may have been reversed for failure to enforce the rule.

Judges expect attorneys to know the rules. Attorneys who practice in multiple courts may need to learn and use many sets of rules. Just do it. The alternative is to be sorry. Courts are not gentle with attorneys who fail to read and follow the rules, as reflected in the following, drawn from a wide variety of available examples. In some instances, the court decision effectively sets up a malpractice action against the careless attorney.

Rules do not normally determine the merits, although rules provide the structure or framework within which the merits can be considered fairly to both sides. Not surprisingly, judges typically know the applicable rules quite well. The judge may have drafted the local rule specifically to address an issue arising with some frequency in that judge’s courtroom. Or the judge may have been reversed for failure to enforce the rule.

Judges expect attorneys to know the rules. Attorneys who practice in multiple courts may need to learn and use many sets of rules. Just do it. The alternative is to be sorry. Courts are not gentle with attorneys who fail to read and follow the rules, as reflected in the following, drawn from a wide variety of available examples. In some instances, the court decision effectively sets up a malpractice action against the careless attorney.