20 Jun Ninth Circuit: Ordinance Criminalizing Living in Car Is Unconstitutionally Vague

If you eat, talk on the phone, and escape the rain in your car, are you using the car “as living quarters either overnight, day-by-day, or otherwise?”

What if you load up the car with personal belongings for a camping trip? Or drive an RV to go on vacation?

In the Ninth Circuit’s view, a City of Los Angeles code provision designed to outlaw sleeping in a vehicle on City streets and parking lots may or may not criminalize all these activities and could lead to other selective enforcement—particularly against the homeless and poor. The court therefore ruled that the provision is unconstitutionally vague. The decision is Desertrain v. City of Los Angeles, No. 11-56957 (June 19, 2014).

Los Angeles Municipal Code Section 85.02 outlaws using a vehicle upon a City street or parking lot “as living quarters”:

USE OF STREETS AND PUBLIC PARKING LOTS FOR HABITATION.

No person shall use a vehicle parked or standing upon any City street, or upon any parking lot owned by the City of Los Angeles and under the control of the City of Los Angeles or under control of the Los Angeles County Department of Beaches and Harbors, as living quarters either overnight, day-by-day, or otherwise.

Applying City of Chicago v. Morales, 527 U.S. 41 (1999), the Ninth Circuit explained that a criminal statute may be unconstitutionally vague for either of two independent reasons:

- It may “fail to provide the kind of notice that will enable ordinary people to understand what conduct it prohibits”; and

- It may “authorize and even encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement.”

The Ninth Circuit ruled that the City’s ordinance fell short on both measures.

On the first, “there is no way to know what is required to violation Section 85.02″:

Plaintiffs are left guessing as to what behavior would subject them to citation and arrest by an officer. Is it impermissible to eat food in a vehicle? Is it illegal to keep a sleeping bag? Canned food? Books? What about speaking on a cell phone? Or staying in the car to get out of the rain? These are all actions Plaintiffs were taking when arrested for violation of the ordinance, all of which are otherwise perfectly legal. And despite Plaintiffs’ repeated attempts to comply with Section 85.02, there appears to be nothing they can do to avoid violating the statute short of discarding all of their possessions or their vehicles, or leaving Los Angeles entirely. All in all, this broad and cryptic statute criminalizes innocent behavior, making it impossible for citizens to know how to keep their conduct within the pale.

And, according to the court, Section 85.02 encourages arbitrary enforcement: it is “broad enough to cover any driver in Los Angeles who eats food or transports belongings in his or her vehicle . . . . [y]et it appears to be applied only to the homeless.” The court noted that officers had inconsistent views about how and when the statute should be applied. The lack of clarity has “paved the way for law enforcement to target the homeless.”

Although the court acknowledged that the ordinance may have been motivated by legitimate health and safety concerns, it ruled that these concerns do not excuse the fact that the ordinance fails to speak clearly. The court also refused to apply a limiting construction based on the City’s enforcement because the City had not followed any consistent practice.

The court concluded by emphasizing that the City should address homelessness in other ways:

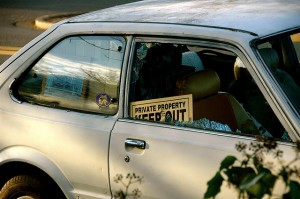

For many homeless persons, their automobile may be their last major possession — the means by which they can look for work and seek social services. The City of Los Angeles has many options at its disposal to alleviate the plight and suffering of its homeless citizens. Selectively preventing the homeless and the poor from using their vehicles for activities many other citizens also conduct in their cars should not be one of those options.

Image courtesy of Flickr by Don Hankins (creative-commons license, no changes made).